The End of the Russian Oligarchs

From Shock‑Therapy Billionaires to Kremlin Bondservants -Rafael Benavente

From Shock‑Therapy Billionaires to Kremlin Bondservants

I. The Birth of the Oligarchs: Chaos and Opportunity

In the early 1990s Russia was in free fall. The Soviet Union had collapsed, inflation ran at four‑digit rates, and Boris Yeltsin’s government embraced Western‑advised “shock therapy.” State‑owned oil fields, smelters, and banks were hurriedly auctioned off through vouchers and insider loans.

A handful of men—Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Boris Berezovsky, Roman Abramovich, Vladimir Potanin, and others—understood how to game the infant market system. For kopeks on the ruble they bought entire industries, then resold commodities abroad for hard currency.

Their wealth soon bought political influence. In 1996 the same tycoons financed Yeltsin’s re‑election in exchange for still more assets and regulatory favors. Media empires like ORT and NTV became both profit centers and electoral weapons. By decade’s end, Russia’s “oligarchs” weren’t just businessmen; they were king‑makers.

II. Putin’s Rise: Partnership Turns to Purge

When an obscure FSB veteran named Vladimir Putin entered the Kremlin on New Year’s Eve 1999, many moguls assumed he would be easy to manage. They were disastrously wrong.

Putin saw the oligarchs as both a threat and an opportunity. His first move was a tacit bargain:

“Keep your money, stay out of politics.”

Those who agreed, like Abramovich, prospered. Those who challenged him—most famously Khodorkovsky, who funded opposition parties—were crushed. In 2003 Khodorkovsky was arrested, Yukos was dismantled, and its prime assets folded into state‑run Rosneft. The message was unambiguous: Kremlin > Capital.

III. A Shift in Power: From Oligarchs to Siloviki

With Khodorkovsky’s show trial, the oligarch model cracked. Real influence migrated to the siloviki—veterans of the security services, generals, and state‑enterprise bosses whose fortunes rose and fell at Putin’s whim.

Companies such as Gazprom, Rosneft, Rostec, and defense conglomerate Rostec swelled by absorbing “voluntarily donated” private assets. This was not nationalization in a socialist sense; it was Kremlin consolidation. Wealth still belonged to a few, but those few now owed everything to the state—and could lose it overnight.

IV. 2022: The Ukraine Invasion and Global Sanctions

The full‑scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 marked the beginning of the end for the jet‑set oligarch lifestyle.

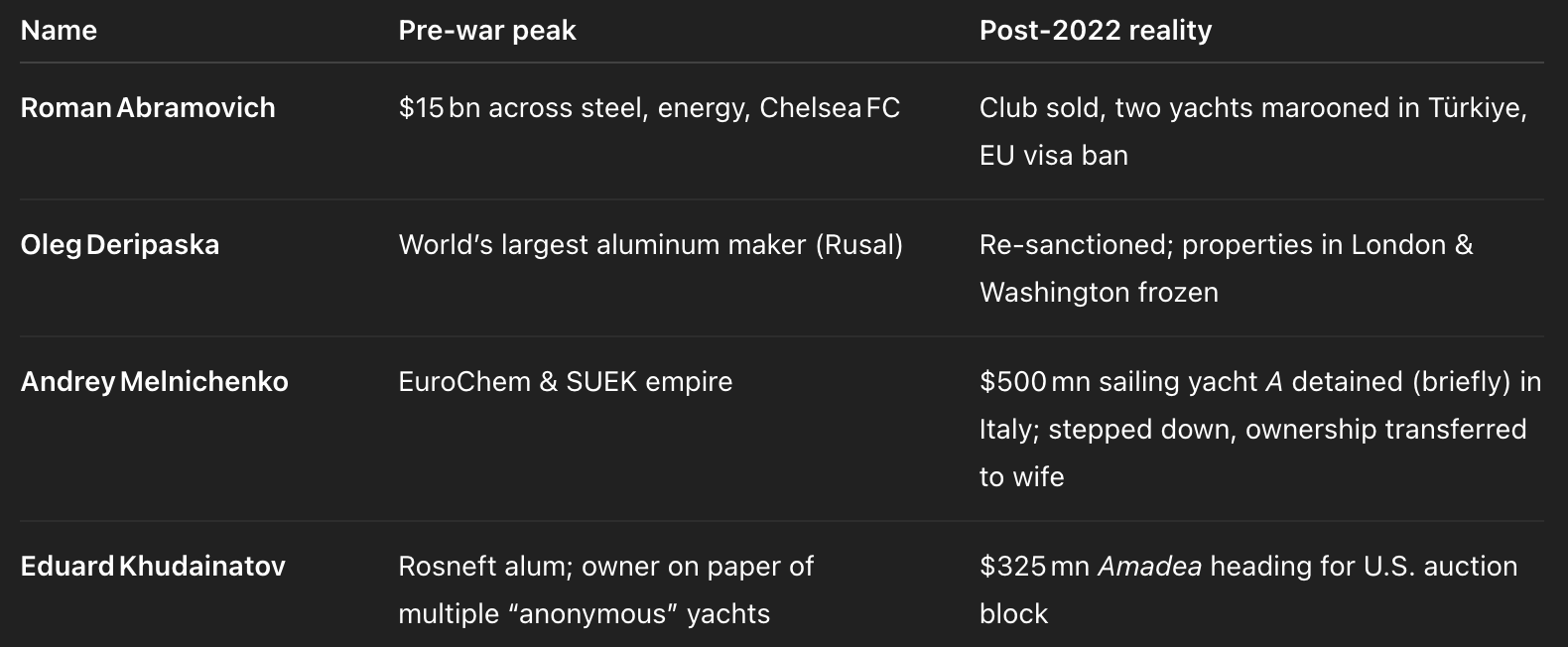

- Eighteen rounds of EU sanctions (and counting) froze billions of dollars in assets.

- Super‑yachts like the Amadea were seized from Fiji to Spain and cleared for auction to fund Ukrainian reconstruction.

- Abramovich was forced to sell Chelsea FC under U.K. pressure; other trophy assets from luxury villas to private art collections were confiscated or fire‑sold.

- The U.S. and EU began piercing offshore trusts, exposing complex nominee structures that once hid true ownership.

The oligarchs, who had long parked wealth in London, Cyprus, and New York, suddenly discovered that offshore is not off‑limits when geopolitics turns hostile.

V. The Fall of the Jet‑Set Elite

Lavish travel is over; foreign bank accounts are unreachable; reputational risk makes even neutral jurisdictions wary. The defining status symbol of the 2000s—“Londongrad” real estate—now trades at distressed prices or stands empty under legal dispute.

VI. Mysterious Deaths and Convenient Accidents

Compounding the financial squeeze is a macabre roll‑call of sudden fatalities:

- Ravil Maganov (Lukoil chairman) plummets from a Moscow hospital window.

- Sergey Protosenya (former Novatek executive) found dead with family in Spain.

- Leonid Shulman (Gazprombank) reported suicide under murky circumstances.

At least a dozen energy and banking executives have died since 2022. Whether forced suicides, Kremlin clean‑ups, or genuine tragedies, the pattern amplifies fear: wealth no longer guarantees personal safety.

VII. The New Power Elite: Putin’s Inner Circle

As the old guard is sidelined, a new court nobility rises—men whose entire fortunes depend on budget allocations, defense contracts, and security‑service patronage.

- Igor Sechin – CEO of Rosneft, nicknamed “Darth Vader” in Moscow circles.

- Yuri Kovalchuk – principal shareholder of Bank Rossiya, believed to manage Putin’s personal finances.

- Sergey Chemezov – head of Rostec, orchestrating the militarized industrial complex.

These figures are not entrepreneurial oligarchs; they are custodians of state power, rewarded for loyalty and punished for the slightest hint of dissent.

VIII. What Replaces the Oligarchy?

Russia is morphing into a bureaucratic autocracy where capital, policy, and coercion flow from a single center. Private ownership persists on paper, but true control rests with ministries, security services, and the presidential administration.

- Windfall levies (10 % in 2023) and a permanent corporate tax hike (from 20 % to 25 %) make business a form of forced subscription to the war effort.

- Capital‑repatriation rules keep 80 % of hard‑currency export earnings onshore.

- Progressive income tax tiers (up to 22 %) erode Russia’s long‑boasted flat‑tax advantage.

Innovation suffers, foreign investors flee, but political stability—measured as personal loyalty to Putin—tightens.

IX. Global Consequences

- Economic Warfare Redefined

Targeting yachts and football clubs proved that sanctions can directly assault elite lifestyles, not just macro indicators. Western democracies discovered a powerful new lever: luxury interdiction. - Warning to Other Authoritarians

Beijing, Riyadh, and Caracas took note. Offshore wealth is no longer immune when geopolitical winds shift. Expect diversified asset geography—and heightened paranoia—among global strongmen. - Long‑Term Drag on Russia’s Economy

Capital flight, tech‑sector brain drain, and the chilling effect on private initiative threaten growth beyond hydrocarbons. Russia leans harder on China and India, trading discounts for diplomatic cover.

X. Is It Truly the End?

Skeptics argue the oligarchs are merely in hibernation—riches tucked away in shell companies and Caribbean trusts. Yet one critical change is undeniable: they no longer hold political power. Without the ability to lobby, bankroll parties, or shape policy, an oligarch is just a high‑net‑worth captive.

Conclusion: A Cautionary Tale

The rise and fall of Russia’s oligarchs is a modern parable. Shock‑therapy capitalism created instant billionaires; unchecked presidential power turned them into hostages to the state.

What began as an experiment in post‑Soviet privatization ends with yachts impounded, fortunes fenced in, and a ruling class that trades cash for unquestioning loyalty.

The age of the oligarch is over. What replaces it—a centralized war economy run by siloviki and technocrats—may prove even less transparent and more dangerous for Russia, its neighbors, and global markets.

If you found this analysis useful, explore my related piece “Klepto‑Capture: How Seized Yachts Could Rebuild Ukraine” for a deeper dive into asset forfeitures and their legal hurdles.

By Rafael Benavente

For a deeper look at how Russia’s geopolitical influence is unraveling beyond its borders—especially in the Caucasus region—read my related article on the growing tensions between Azerbaijan and Russia:

👉 Azerbaijan vs. Russia: How Baku Is Breaking Free from Moscow’s Grip

For more insights into Russia’s weakening grip beyond its borders, explore these related articles:

- 🇺🇦 Can Ukraine Retake Crimea? A Strategic Path Through Siege and Patience — A deep dive into Ukraine’s long game to reclaim Crimea without a direct assault.